Can Markets Regulate Themselves?

Sometimes, governments regulate markets. And sometimes, market participants regulate themselves. The outcome can be surprisingly different; thankfully, we have several examples that can serve as case studies.

People arguing about regulation tend to favor one side of the argument and believe that either the government or the market has the capabilities and the desire to standardize and solve consumer problems. Theoretically, both approaches are valid, even if they lead to different outcomes. I wanted to tell you about two particular examples I like the most. And yes, basically I will compare the United States and the European Union.

First is credit card cashback. But we need to take a few steps back first. When you buy something for $100 with a VISA or MasterCard, the seller doesn’t get $100. There are interchange fees charged by the card processing network that are shared between them, the bank operating the card terminal, and your own bank.

This creates a few challenges. The seller gets less money, but in theory, you’re more likely to spend more at their establishment if you can pay with a card. Still, they most likely keep their prices a tiny bit higher to account for this loss. The interchange fees also aren’t totally linear. The advertised Stripe US rate is a good example: 2.9% + 30¢ for each successful card charge. A brick-and-mortar business is more likely to use something like Square, which offers 2.6% + 10¢. But there’s always this fixed part, which makes fees on a small purchase much larger.

If you buy something for $100 with Stripe, the seller will receive around $96.8 (or lose 3.2%). But if the charge is just $5, the seller will get $4.55 (or lose 9%). This makes small amounts very inconvenient and potentially outright unprofitable for the seller. This is also one of the reasons Twitch sells its ‘Bits’ in huge chunks and Apple combines AppStore purchases to charge you once when it can.

Interchange fees are essentially a tax on most consumer transactions in a cashless economy, inflating prices and making certain transactions financially impractical. How do we solve this?

The competition between banks in the US (and some other countries) led them to invent cashback. Instead of pocketing their share of interchange fees as revenue, they give it back to their users to attract and retain their customers. Preferably high-value customers. The kind who will generate revenue for these banks through other products. US banks could pay between 1.5-3% in cashback, depending on a particular card program and purchase category. Technically, they might even overpay and lose money on certain benefits, but the cashback is the key source here.

Cashback addresses the inflated prices, but not ideally, and this is only one of two problems introduced by interchange fees. A policy study conducted by the Federal Reserve concluded that back-reward programs result in a monetary transfer from low-income to high-income people. This makes sense since the best terms of cashback and rewards are available on premium cards.

The Durbin Amendment in 2010 limited transaction fees to 21 cents plus 0.05% of the transaction value for banks with $10 billion or more in assets—but only for debit cards. This is also why many American challenger banks and fintech startups, like Evolve Bank, meticulously chose the partners who’d provide them with this source of revenue.

To clarify, there’s nothing unique about credit cards, as debit cards with cashback are quite common in other countries.

The European Union chose another route. Regulation (EU) 2015/751 limited interchange fees for card-based payment to 0.2% of the transaction’s value for debit cards and 0.30% for credit transactions. Effectively, the EU told Visa and MasterCard: “Look, you guys have won. You can enjoy a profitable business with an extreme moat, but we want to limit the negative externalities.”

Before 2015, it was common to see signs allowing card payments for purchases over €10 in European stores. Almost 10 years later, however, these are much rarer (Germany still loves cash, though). European cards basically have no meaningful cashback programs simply because banks don’t have this revenue source. This seems a reasonable trade-off since the prices are also cheaper.

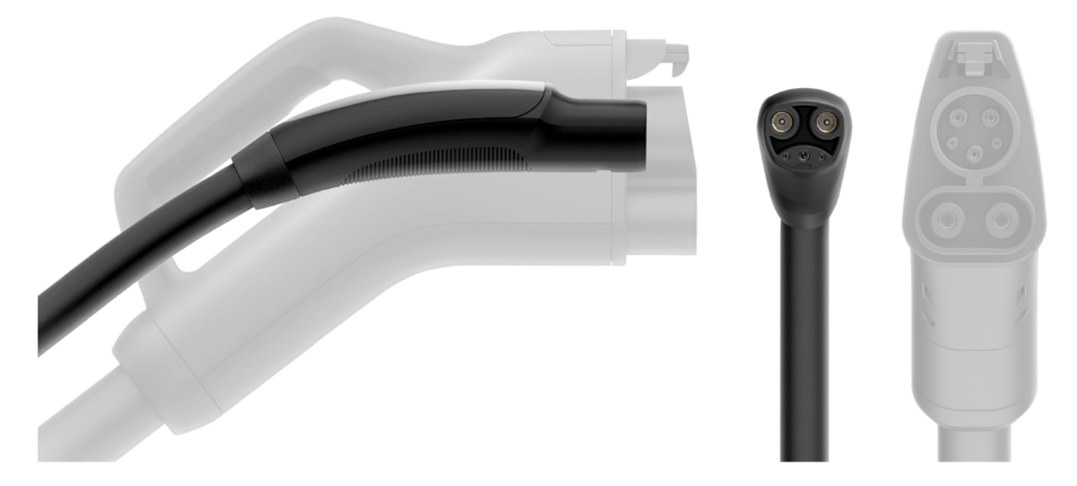

EV Chargers

Charging ports for electric vehicles are another example. The US and Europe have effectively settled on a particular standard—but different ones. The EU uses CCS2, an extension of the old Type2 port with fast charging, and practically all automakers are committed to switching to NACS (Tesla’s port) in the US.

The former is a case of regulation. In 2014, the European Union adopted CCS2 as a requirement for EV charging networks. The latter is a case of Tesla building the largest charging network in the US to the point that other automakers found it easier to switch (without anybody forcing them).

From the user perspective, NACS looks better as it’s much smaller and lighter. From a technical perspective, CCS2 might actually be better, at least for Europe, with its supposedly superior electric grid with 240V and 3 phases.

We’re still a little bit away from all cars having the same ports. In Europe, cars and stations with outdated ports like CHAdeMO still exist, while older Teslas use their proprietary CCS extension. Automakers will only start shipping NACS-enabled cars in the US by 2025, so everyone with an older vehicle like a Rivian R1S/R1T will likely have to upgrade or start using an adapter for Tesla’s Superchargers or new public chargers.

These two approaches have two drastically different outcomes, yet both solve the enormous problem of multiple incompatible ports and chargers.

***

Markets tend to solve consumer problems with the means available, but the outcome is often quite different from a potential government intervention. Both options could also just fail, resulting in a dysfunctional market or an incapable government monopoly.

What’s common between them is the reliance on the pre-existing situation. Anything dominant tends to have a moat. What’s different is the focus on negative externalities. It seems that in the cases of markets regulating themselves, these externalities persist unless some actors are both incentivized to eliminate them and have the capacity to do so.