Superhuman and Premium Software

Superhuman with its premium pricing of $30 per month expands the Overton windows for apps pricing and has already enabled higher (and more sustainable prices) for new companies.

Superhuman is an app that has been reviewed and discussed from top to bottom, we’ve seen countless mentions of “Superhuman for X”, discussions of “consumerization of enterprise” and I saw Rahul Vohra’s Product-Market Fit score estimations in dozens of startups’ decks at this point.

But I always felt that one topic has remained largely in shadow: how Superhuman moved the Overton window of apps pricing.

A Bit of History

Back in the days software was quite expensive. The list price of Photoshop 1.0 for Macintosh in 1990 was $895 (that’s $1,767 in today’s dollars). In 2011 it was priced at $699. Not everyone paid those prices of course. I even had a theory that Adobe specifically wasn’t fighting the piracy of their products (their protection was very basic) for individual users because it acted as a top of the funnel. Teens would learn Photostop and Illustrator to draw and publish something on DevianArt. Some of them would become designers and come to a workspace expecting to see Adobe products there. All good! In comparison, local Adobe offices were pretty adamant about piracy at workspaces.

Generally, software was distributed via the sharewave model through various catalogs and websites. Even smaller utilies could cost $10/$20/$50 because not a lot of people would discover them in the first place and even lesss people would pay. “Professional” software was expensive but individual users weren’t the buying personas for it and the prices didn’t matter that much.

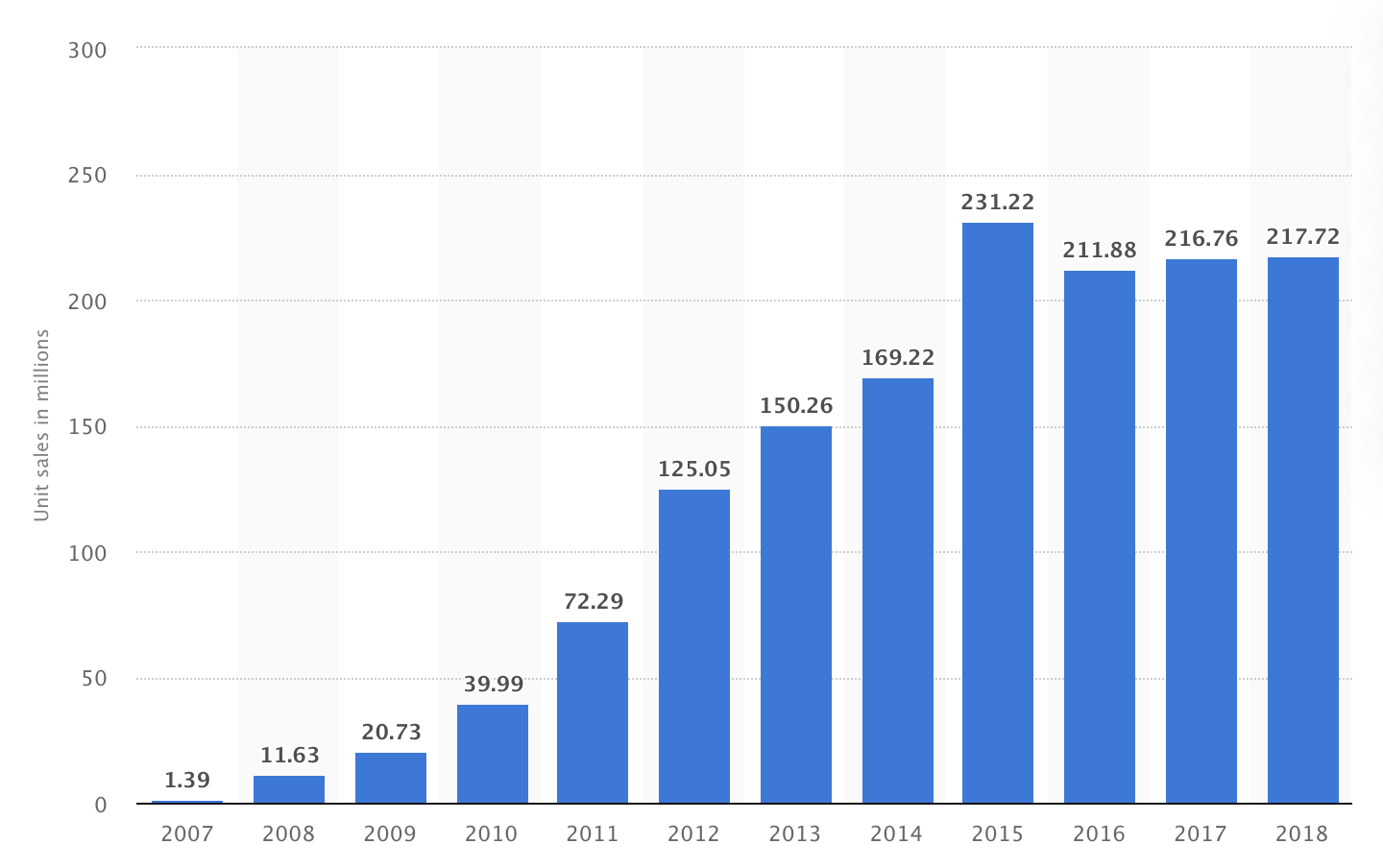

Then came the mobile. Apple AppStore redefined the pricing of mobile apps and games. Every month millions of people were buying new smartphones and becoming new users for the apps in the store. Trying to compete for them, the developers have driven the costs way down. Now people expected apps to be either free or a couple of dollars – $5 is already quite expensive!

But then somethign changed. The market has become saturated. People are still buying new phones, but less often – and they already have previous iPhones (or Android phones) and had the apps they needed. One-time small purchases were no longer able to drive the revenue.

But then somethign changed. The market has become saturated. People are still buying new phones, but less often – and they already have previous iPhones (or Android phones) and had the apps they needed. One-time small purchases were no longer able to drive the revenue.

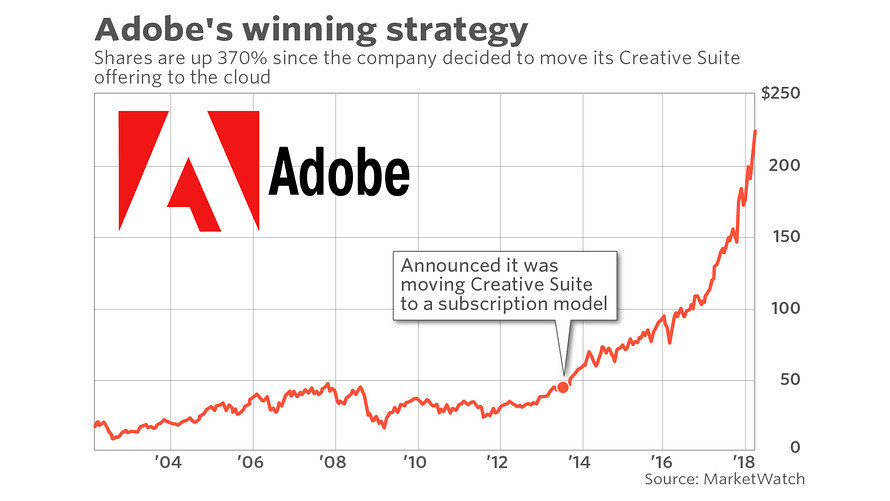

Apple initially offered subscription pricing on AppStore in 2011 but only for content. Subscriptions for apps appeared in 2016. Meanwhile, Adobe switched to SaaS-only model in 2013.

Since then multiple old apps, including Fantastical, 1password, Ulyssess and many others have switched. Subscriptions incentivize developers to care about their existing userbase and provide recurring revenue to fund the development.

In 2016 Recode wrote that “The app boom is over”, an editorial in TechCrunch stated that “The air of hopelessness that surrounds the mobile app ecosystem is obvious and demoralizing”, and The Verge wrote that “the original App Store model of selling apps for a buck or two looks antiquated”.

Originally, the subscription pricing wasn’t that scary. Things 3 for iOS/iPadOS/MacOS costs a few years of Todoist Premium costs, which makes them relatively comparable. The developers weren’t ready to charge much more for consumer-grade software.

The New Age

Superhuman shocked a lot of people with its $30/month pricing for an email client (that’s $360 per year). I believe that this greatly extended the “Overton window” for consumer software pricing and enabled other companies to charge 2-3x more of what they initially did.

There have been a few email clients before that and most of their either:

- Were acquired by large tech companies for reasons unrelated to their core business [1], [2]

- Failed drastically [1]

- Were noticed selling insights based on users’ communications [1]

Turns out it’s very hard to make a good email client. Even while they were alive, most of those apps weren’t polished enough.

What if you can do a better job but need to charge more money? You probably need to ask if there’s a market for this. Designers would spend their entire days in Photoshop or Illustrator. There are different pricing plans, but a monthly single-app subscription is about $30. What if the user spends an entire day in email? Does it worth it? I guess so.

What’s even more interesting, such pricing allows the products that earlier could only be small utilities supported by indie teams turn into venture-backed companies. Regular pricing, especially one-time purchases, can’t really enable the margins and growth rate needed. You can think of Evernote that wasn’t able to recover to its early expectations.

Now we’re seeing dozens of old and new apps embracing higher pricing. One of the common aspect is that you can technically find more primitive ancestors for the newcomers that were simpler and charged less.

- Roam Research, a “a note-taking tool for networked thought” that became quite mainstream on Twitter recently, is touting a price of $15 a month as they come out of their current “early-access” status.

- Sunsama, a better task management and calendar app, is $20 a month ($16 with an annual discount).

- Fanstastical, a great email app for Apple’s platforms, used to cost $49.99 for a Mac app as a one-time purchase, now it costs $5 a month ($40 a year with an annual discount).

- Linear, a better issue tracker, is expected to be aroud $10/month when they come out of beta.

- Command-E, a less hacky Alfred for Mac, is expected to be aroud $10/month when they come out of beta.

If you have any other examples, please share, I’d be happy to add them.

What’s Next?

The tools we use in our digital lives are mostly subpar. They rely on the decades-old principles. Consumer software has been optimized for the mass user resulting in the lowest denomiator effects – Gmail is used by 1 billion people so it has to work for 1 billion people. Enterprise software instead has been optimized for entire organizations and the buying persona. The CIO might love the product but it’s not necessarily the best for individual contributors.

There are now two combining effects: the widely discussed consumerization of enterprise, meaning that software is adopted bottom-up and optimized for the experience of individual users, but also the expanding realization that companies can charge way more for personal productivity tools – and use that revenue and expectation to build better tools.