Communicating with Numbers

If you can find a figure that makes your business more appealing than competitors, you should run with it.

One of the strongest moves in communications is pushing slightly wrong numbers out so that many people start quoting them and associate with your business (or your competitors) forever.

Two of my favorite examples are Stripe and Apple Music. Let’s dig in.

Stripe famously charges 2.9% + $0.30 per transaction. Well, on average, they charge more. This pricing only applies at the base level and for bank cards issued in the United States. Any foreign card adds 1%. There are charges related to addon products you might use, from Stripe Subscription to something more specific.

But many people quote the advertised figure, which acts as an anchor. I know Stripe alternatives for some local markets that heavily promote the fact they’re a bit cheaper once you include all these charges.

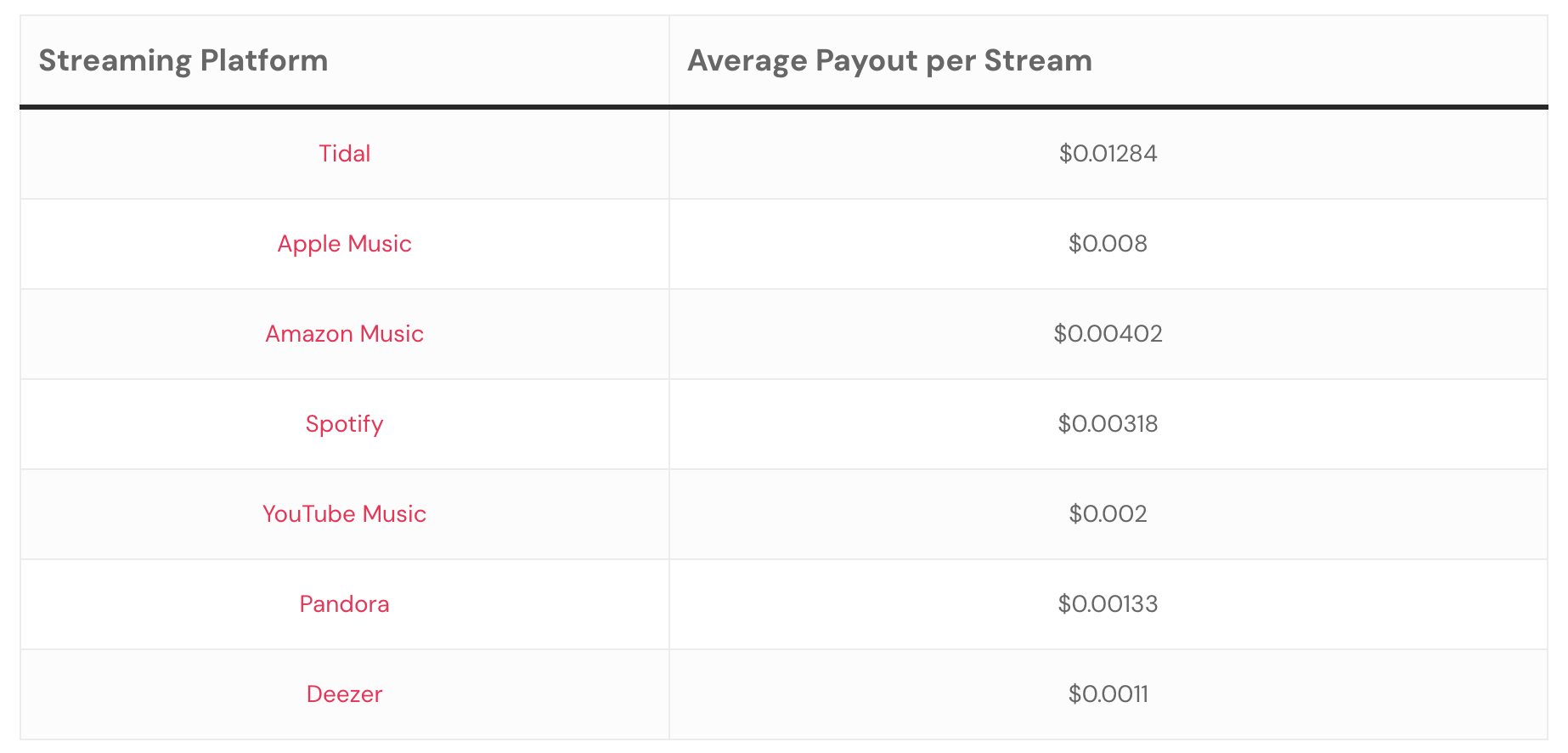

Now to Apple Music. When you read news about the streaming business, you might often see the “price per stream” figure. This is how much each of the streaming services, including Apple Music, Spotify, and all others, pay the right holders (labels, musicians, producers, and everyone else collectively) for each separate stream of their track.

The figures change over the months and years, but Apple Music consistently looks better than Spotify. Look, they pay more! It means they care about artists! Right?

The “price per stream” doesn’t really make much sense. This isn’t how streaming platforms pay. Nobody is instituting a specific payout price each month.

If we simplify, it looks like this. Spotify earned X billion dollars last month through subscriptions and ads. During this month, users collectively consumed Y billion streams. If you divide X by Y, you get the price per stream, but it’s not set, it varies each month. Each particular artist is getting more money from Spotify than Apple Music. Spotify simply has more users. It’s also a bit more aggressive in adjusting its pricing to local markets, and unlike Apple Music, it has an ad-supported tier, which brings less revenue per user.

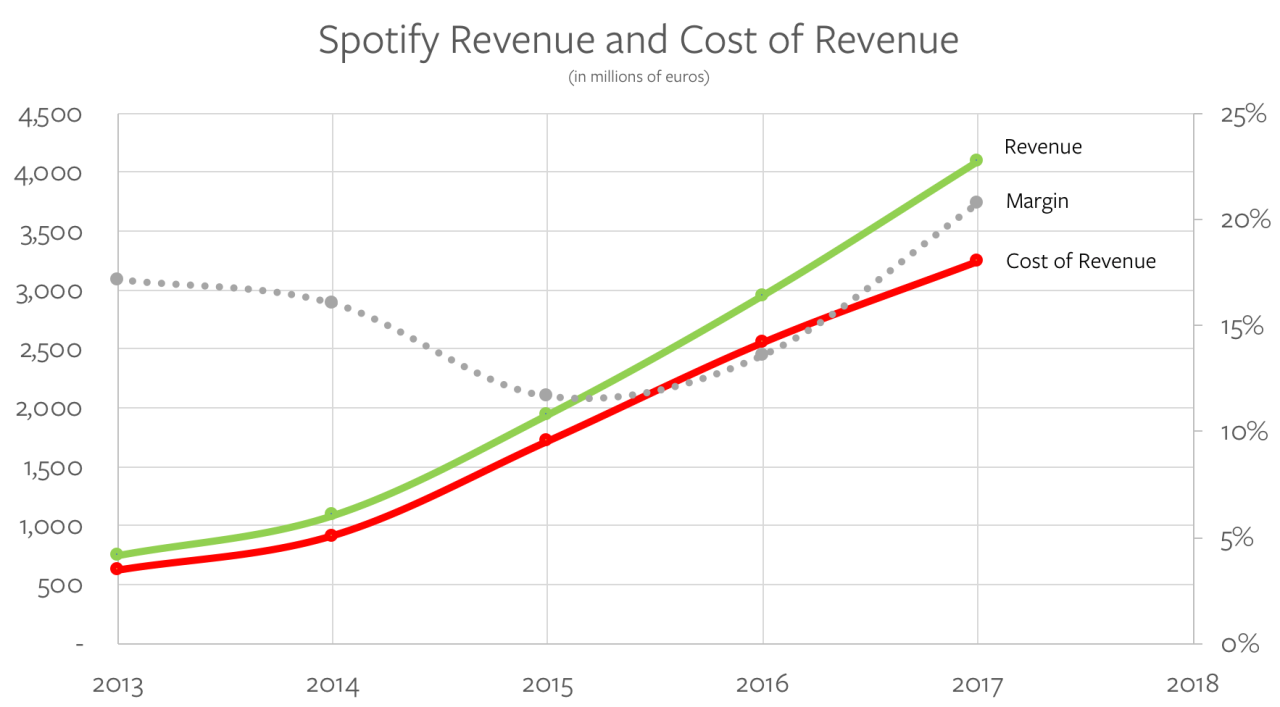

If you look at Spotify’s quarterly results, there’s a Cost of Revenue line, which is consistently around 74% – this is the share of the total revenue they pay out to artists and rights holders. The company itself has been unprofitable until very recently. If you still want to claim that Spotify underpays artists, it largely comes down to their relationships with labels and music just isn’t a very big industry (and it never was).

But if you look at “price per stream”, Apple Music looks better.

***

The key rule of communication is that the larger your audience, the simpler your message should be. This is one of the reasons politics inevitably turns into populism since you have to condense your entire program into a slogan, whether it’s “Make America Great Again” or “Break up Big Tech’“.

And it’s hard to find something simpler than a number. If you can find a figure that makes your business more appealing than competitors, you should run with it. The best case, of course, is when your business structure allows you to make your competitor’s primary revenue line a free addon. A good example here would be the launch of R2 by Cloudflare. Amazon Web Services charge developers a lot of money if they want to move data out of the network. They call it egress fees. Cloudflare just made it free.