IMAX is a Superbrand

Superbrands create and control key technology allowing them to break the common laws of branding and put themselves forward. Here’s how IMAX put an intro in front of every movie.

How many companies building cinema projectors do you know?

I bet you know at least one, and it’s called IMAX. You’ve heard the name when you watched “Dune“, “Avatar“, or something from Christopher Nolan. If you paid more to get an IMAX experience, they weren’t too shy to add a dedicated intro promoting themselves — quite obnoxious if you ask me.

Do you get how weird it is? I mean, do you know any other projectors? Yet IMAX has become entangled with the film industry and a sign of prestige. There are 1,772 IMAX theaters across 90 countries. A huge scandal played out when Tom Cruise couldn’t secure extended IMAX viewings for his previous Mission Impossible film.

Lately, I’ve become exceedingly interested in companies with brands so powerful that they break common laws. This is my first post in this new series, and I have a few others in the pipeline.

Companies are egoists by nature. They don’t want to share the spotlight, and they don’t want any other brand alongside their own. So when they do, it’s a beautiful exception worth exploring.

Like other Superbrands, IMAX has conquered its dominant place by inventing and controlling a unique technology that enabled the industry to go beyond what was possible. It became a symbol of quality, which meant partners benefited by advertising their films as IMAX.

In this story, I want to answer several questions:

- What is IMAX

- How did it emerge

- And what enabled it to secure this supreme position

What is IMAX

IMAX is a cinema format that combines specialized cameras, a specific post-production pipeline and purpose-built cinemas to deliver a superior viewing experience.

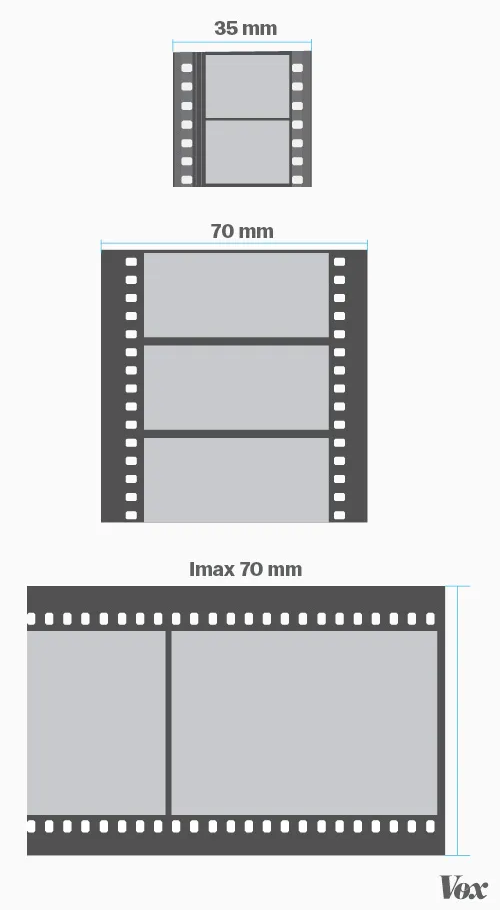

The standard film format was 35mm. In addition to doubling it and using 70mm, IMAX also changed the orientation. Instead of feeding the film vertically like in standard projectors, IMAX runs the film sideways (horizontally) and makes each frame much taller.

In regular 70mm film, a frame is usually 5 perforations tall and runs vertically through the projector. But with IMAX’s 70mm, each frame is 15 perforations wide (the official name is 15/70). This lets each frame stretch across more of the film’s width, making it about 10 times bigger in area than standard 35mm film. While top digital cameras can reach the 8K resolution, IMAX film achieves roughly 16K.

(And while I’m already scared of confusing you, it’s important to remember that 70mm is the projection film, while IMAX is actually shot on 65mm film, as 5mm is used for the soundtrack)

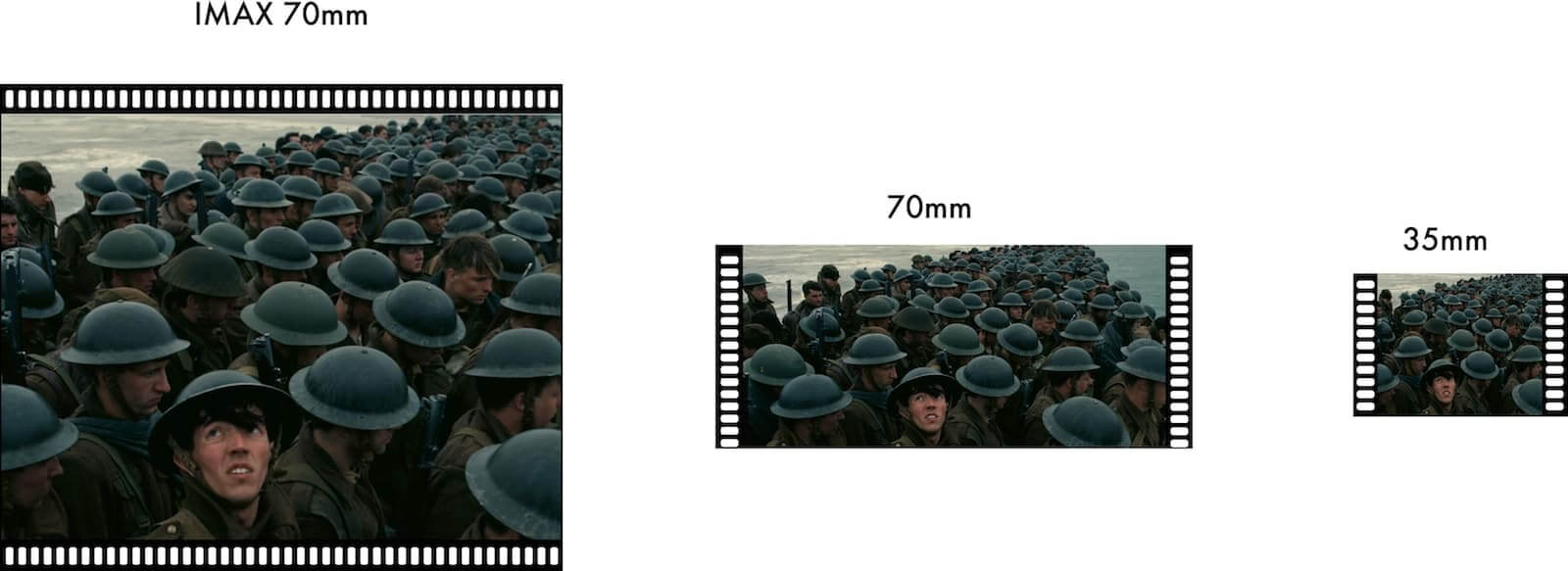

This is what gives IMAX its square-ish 1.43:1 ratio — when you get to a cinema, you see a much taller screen that can occupy your entire area of vision.

You can find many comparisons of shots in famous movies at IMAX and other carriers. Every other format is cut and pales in comparison. You simply cannot experience the original IMAX cut at home. Even if the movie was shot with IMAX 15/70 cameras (like Dunkirk or Oppenheimer), you’re most likely seeing 1.78:1 or 2.20:1 (closer, still cropped) or even just 2.39:1 (Cinemascope ratio), with IMAX framing lost entirely.

Great, so it’s just a larger film? Not so easy.

The movie industry has been trying to switch from the traditional 35mm to a larger format for decades. Fox introduced Fox Grandeur in 1929, and Walt Disney came up with the Fantasound system for the original “Fantasia” film in 1940. In 1953, CinemaScope was introduced, which brought the now commonly ratio of 2.35:1 (later expanded 2.39:1), much wider than the previously used 1.37:1. It used special anamorphic lenses that compress a wide image onto standard 35mm film, then expand it during projection. All these technologies were targeting the 35mm, and they still tried to keep it. The Techniscope film format was invented and became popular precisely because it used half as much 35mm film for the same number of shots, even at loss of quality.

The Origin Story

In 1967, the International and Universal Exposition was held in Montreal. Two people came there with the same dream of making movies bigger. Making the picture bigger, to be exact.

There, Graeme Ferguson presented his film “Man and the Polar Regions” while Roman Kroitor showcased his production “In the Labyrinth”. Both utilized complex multi-projector and multi-screen systems, which were impressive but challenging. Recognizing each other’s experience, they later decided to pool their expertise and were joined by Robert Kerr, a businessman, and William C. Shaw, an engineer, to form Multiscreen Corporation, Ltd. That company would later change its name to IMAX (Image MAXimum).

Soon, they realized that using multiple film reels and projectors was a dead end and instead decided to focus on one big screen and one big film. In three years, they filed a patent for the “Rolling Loop” film transport system, which allowed for the smooth, high-speed movement of large-format film through a projector.

The Rolling Loop is what enabled the use of 70mm film running horizontally, creating much larger and sharper images than conventional vertical 70mm or 35mm film projectors. The first movie IMAX Corporation produced using this new technology was Tiger Child. To do this, IMAX had to create basically every piece of equipment from scratch, including cameras, lenses, lighting, and sound devices to support their 6-story high screen and giant film frames required for it. The first permanent IMAX theater was established in 1971 in Toronto, Canada.

However, IMAX didn’t become a part of Hollywood for decades after. Throughout the 1980s, IMAX was primarily used for science and nature documentaries as the company expanded across science centers, museums, and planetariums. In 1984, NASA even brought IMAX cameras to space aboard the Space Shuttle Challenger. The audiences were amazed by the picture, but it wasn’t going to conquer cinemas just yet.

IMAX had a chicken-and-egg problem. The 70mm film was expensive, heavy and difficult to operate; the same applied to cameras, which were so loud that you would have to re-record all the actors’ dialogues. And since nobody was shooting movies in IMAX, cinemas weren’t interested in investing in it.

The Fateful Acquisition

In 1994, investment bankers Richard Gelfond and Bradley Wechsler acquired IMAX Corporation, and the same year, they took IMAX public by listing it on the NASDAQ stock exchange. They were fascinated by the technology and believed it could have been used for Hollywood. But first, they had to make it better and figure out how to “sell” it.

One of my best sources for this was the interview that Richard Gelfond, who took the role of the CEO, gave to Harvard Business Review and I will be quoting it extensively. The funniest part is that he and his partner merely wanted to flip the company but he ended up making it his life’s work.

Their first challenge was going around the chicken-and-egg problem.

Studios didn’t want to film a movie in our format (which required bulky, expensive cameras and lots of film) unless thousands of theaters were equipped to show IMAX films. Theater owners wouldn’t convert to IMAX until many more IMAX films were available.

Building IMAX was indeed very expensive. For starters, IMAX used to charge cinema multiplexes $1.2 million for the privilege of using their technology. Meanwhile, studios back then had to send individual prints of the movie to each cinema. While a regular set of 35mm would cost about $1,000, each IMAX print would take $30,000 and require a forklift just to get it over to the projection room.

IMAX had to change basically everything about how it operated and the technology itself to make it work. But in the process, they stumbled upon an extremely profitable model that the company continues to use to this day.

First, they started covering the IMAX installations at cinemas themselves at no up-front charge. But in exchange, they took 20% of the box office on that screen, which proved very wise in the long run, albeit a risky endeavor.

But also, as Richard said:

The huge up-front cost was an obstacle, but not the only one. Very few movies were being offered in the IMAX format.

So, in 2001 they figured out how existing movies could be converted to IMAX, which removed the risks for movie studios. IMAX would even cover the costs of the conversion in return for 12.5% of the box office of the IMAX rerun.

Finally, the shift to digital removed the price barriers of both film and film projection systems: $30,000 in film prints were replaced with $150 reusable hard drives. In 2008, IMAX introduced its first digital projection system, which used dual 2K or 4K projectors, making it easier to install IMAX systems in cinemas. This led to a radical expansion of IMAX theaters globally.

They found a win-win-win scenario that incentivized all the parties to participate:

If it costs $10.50 or $11 to see a new release in a theater, a ticket to the IMAX version will cost about $15 or $16. That means that even if the studio pays us 12.5% and the theater owner pays us 20%, they still wind up with more revenue than if the moviegoer had bought a regular ticket.

The main challenge that they had to work around was that:

The Hollywood movie industry is an interconnected system of studios, directors, and theaters that has evolved over 100 years, and it has a traditional way of doing things.

IMAX had to become a part of that system.

The Industry

In 1998, “Everest”, a documentary film about the struggles involved in climbing the mountain, became the first IMAX film to make it to the box-office top ten. But it was still a documentary and IMAX was trying to enter fiction films.

The turning point was when Disney decided to make “Fantasia 2000”, a sequel to the 1940 movie “Fantasia” and play it exclusively at IMAX theaters. It became the first feature-length animated film to be released in the format across 75 theaters.

Christopher Nolan became the first major director to use IMAX in narrative cinema, shooting parts of “The Dark Knight“ (2008) with IMAX cameras. Although the film only had 28 minutes of IMAX footage, that was enough to turn the tide. Then Brad Bird followed with “Mission: Impossible—Ghost Protocol”, which legitimized IMAX as a format for blockbusters.

Visionary directors like Christopher Nolan, James Cameron, and Denis Villeneuve started integrating IMAX technology into their process. IMAX co-opted the best minds of the industry to become their promoters and ambassadors.

Richard Gelfond:

We used to have to beg studios to make films in the IMAX format, but now a lot of Hollywood people say you can’t really make a blockbuster except in IMAX. As a result, we’ve become much more profitable.

And it’s not surprising. When James Cameron’s “Avatar” was released in IMAX theaters in 2009, it became a sensation. The film heavily relied on 3D and IMAX’s immersive format, which provided a unique cinematic experience. “Avatar” grossed over $2.7 billion, and a lot of it came from IMAX.

Christopher Nolan has become explicitly associated with IMAX. He started with “The Dark Knight”, and continued using it more and more for his future movies, so over 70% of ‘Dunkirk’ was shot in it. For “Oppenheimer”, Nolan even ordered a brand-new film stock to be made because IMAX wasn’t available in black-and-white before (but he really wanted it).

There are still some mountains left unconquered. No feature movie to date has been shot entirely on IMAX film (only digitally) due to technical and logistical challenges. Nolan’s “Odyssey“ will be the first.

Lessons

So, what enabled IMAX to become so dominant? Quality, both real and perceived.

Richard says:

Our commitment to quality and providing a cutting-edge entertainment experience, combined with the differentiation we’re able to create by working closely with these key partners, has enabled us to build IMAX into a globally recognized and sought-after brand.

Imagine the giant screen covering your entire field of view and throbbing sound. IMAX has become synonymous with premium cinema. Directors and studios boast how much of their movie is shot in IMAX because this seems to attract the viewers. But all this time, they’re promoting the company that built the cameras and the projectors.

IMAX enabled higher ticket prices, so even with their cut, studios and theaters make more money. But even more importantly, it helps turn movie releases into events, something that every studio wants to achieve.

Combined with effective marketing, IMAX’s technical features have established it as the go-to brand for high-quality, immersive movie experiences. You can expect a certain quality when going to IMAX (I don’t go to any other theaters anymore).

IMAX’s success is due to its execution. The company took an enormous risk by absorbing all of the primary costs from the cinemas and studios to kickstart this network. They have been rewarded handsomely for this, receiving about 20% of the box office from every IMAX film. IMAX became indispensable to the industry and an integral part of it.

That was a very risky strategy that forced them to incur practically all of the costs. The company was on the verge of bankruptcy and delisting multiple times:

At one point in 2001, our stock traded for 55 cents a share, and some of our bondholders began buying equity and trying to force us into bankruptcy. In 2006, we actively tried to sell the company, but our future was so uncertain that no one was willing to pay a reasonable price.

But they managed to succeed, and the payoff was dramatic.

This is the first post in the series. My next article will be about GORE-TEX, which pushed Nike and Arcteryx to put its brand alongside their own, and the company behind it.

Sources

If you would love to learn more about IMAX, here are the best sources I found while researching materials for this article.

- HBR: The CEO of IMAX on How It Became a Hollywood Powerhouse

- Broadcast Beat: The Evolution of IMAX

- The Business Rule: The IMAX Success Story – What Is It & How Did It Succeed?

- Studio Binder: What is IMAX and How It Changed the Way We Watch Movies

- Cinema Waves: A beginner’s guide to IMAX

Extras

Editors usually force you to cut stories, and this makes sense. The shorter they are, the better, as long as you deliver your core idea. But I still wanted to clarify a few more complex things and add asterisks to give you a complete picture.

First of all, it’s important to understand the definitions, as it can be a bit murky. There are different flavors of IMAX, namely “Filmed for IMAX” and “Shot with IMAX”, which often used interchangeably in marketing, but they mean different things technically and artistically.

“Filmed for IMAX” means the movie was shot with an expanded aspect ratio (1.90:1) that fills more of the IMAX screen. The “F1” 2025 movie, directed by Joseph Kosinski, is a good example. This means the filmmakers used traditional digital cameras and worked closely with the company to optimize the movie visually and sonically for IMAX theaters. Examples include “Dune: Part One”, “The Batman” (2022), “Fast X” (2023).

“Shot with IMAX” means a movie or scene was filmed using special large, high-resolution film or digital cameras built by IMAX itself. Scenes shot this way use a taller aspect ratio (1.43:1 ratio), which fills the entire IMAX screen. Examples would include “Interstellar“, “Dunkirk“, “Oppenheimer“, and many others.