The Myths of Venture Capital

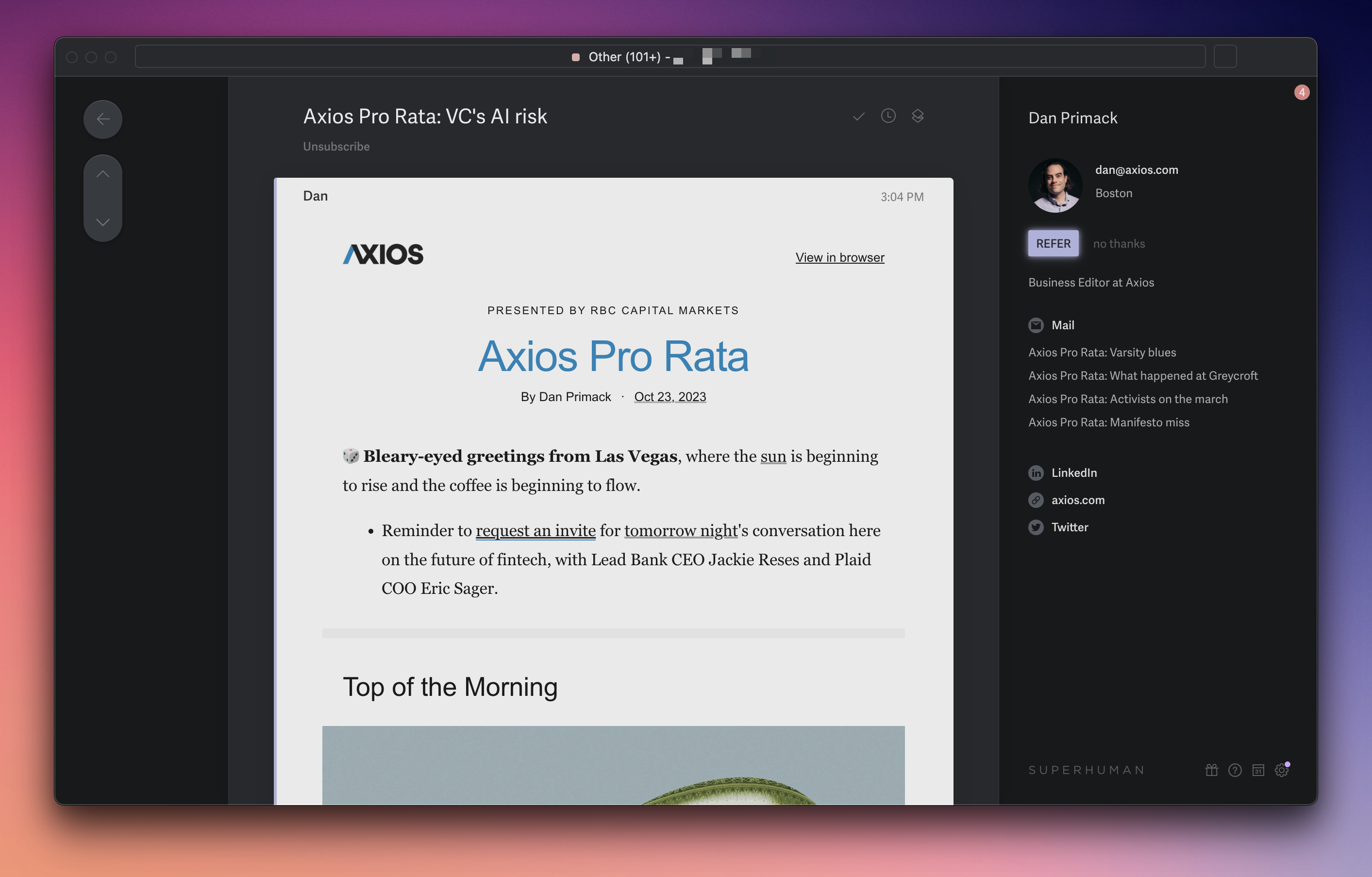

Josh Miller, CEO of The Browser Company in his latest post on finally sunsetting Arc:

So when people ask how venture capital influenced us — or why we didn’t just charge for Arc and run a profitable business — I get it. They’re fair questions. But to me, they miss the forest for the trees. If the goal was to build a small, profitable company with a great team and loyal customers, we wouldn’t have chosen to try and build the successor to the web browser – the most ubiquitous piece of software there is.

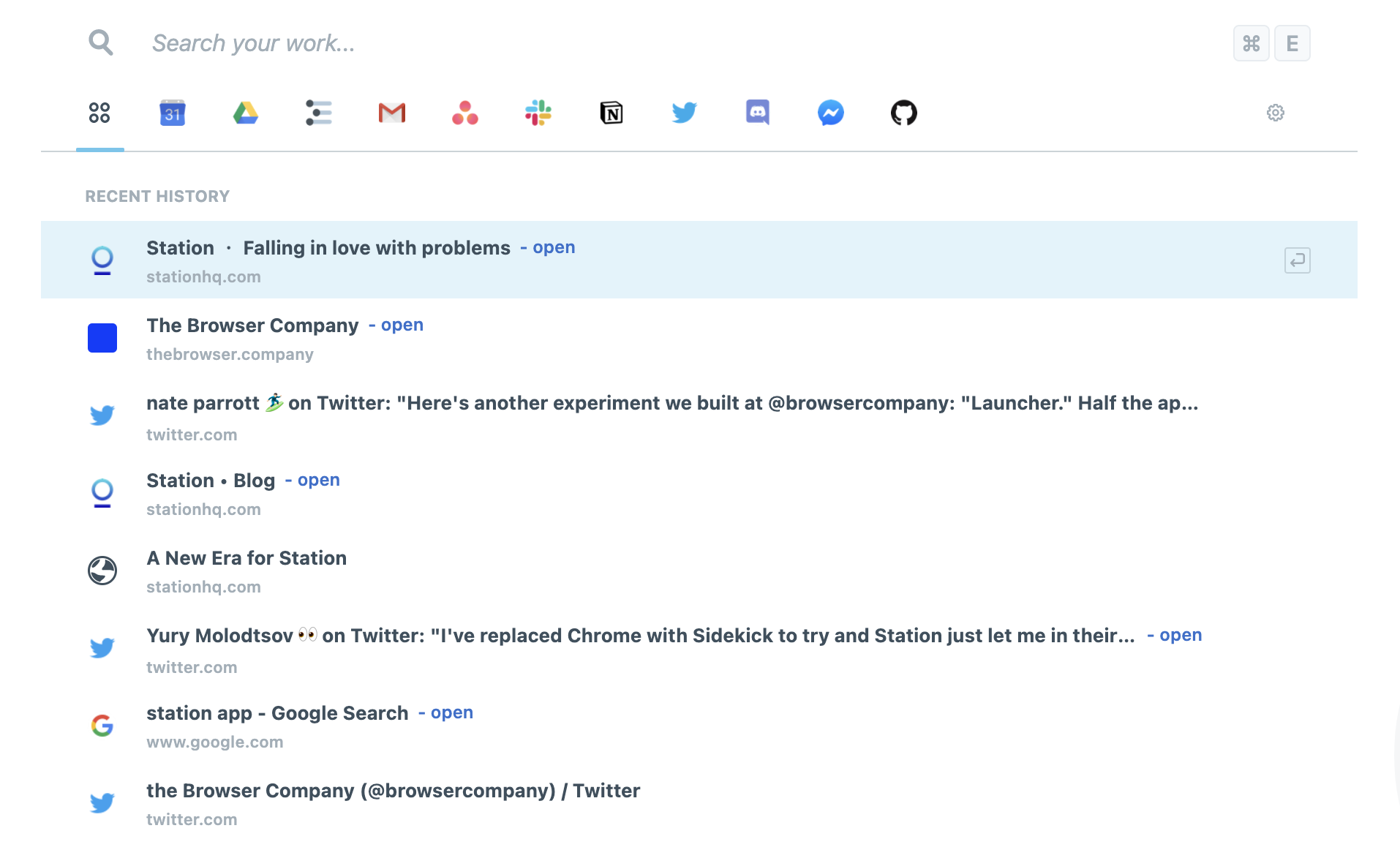

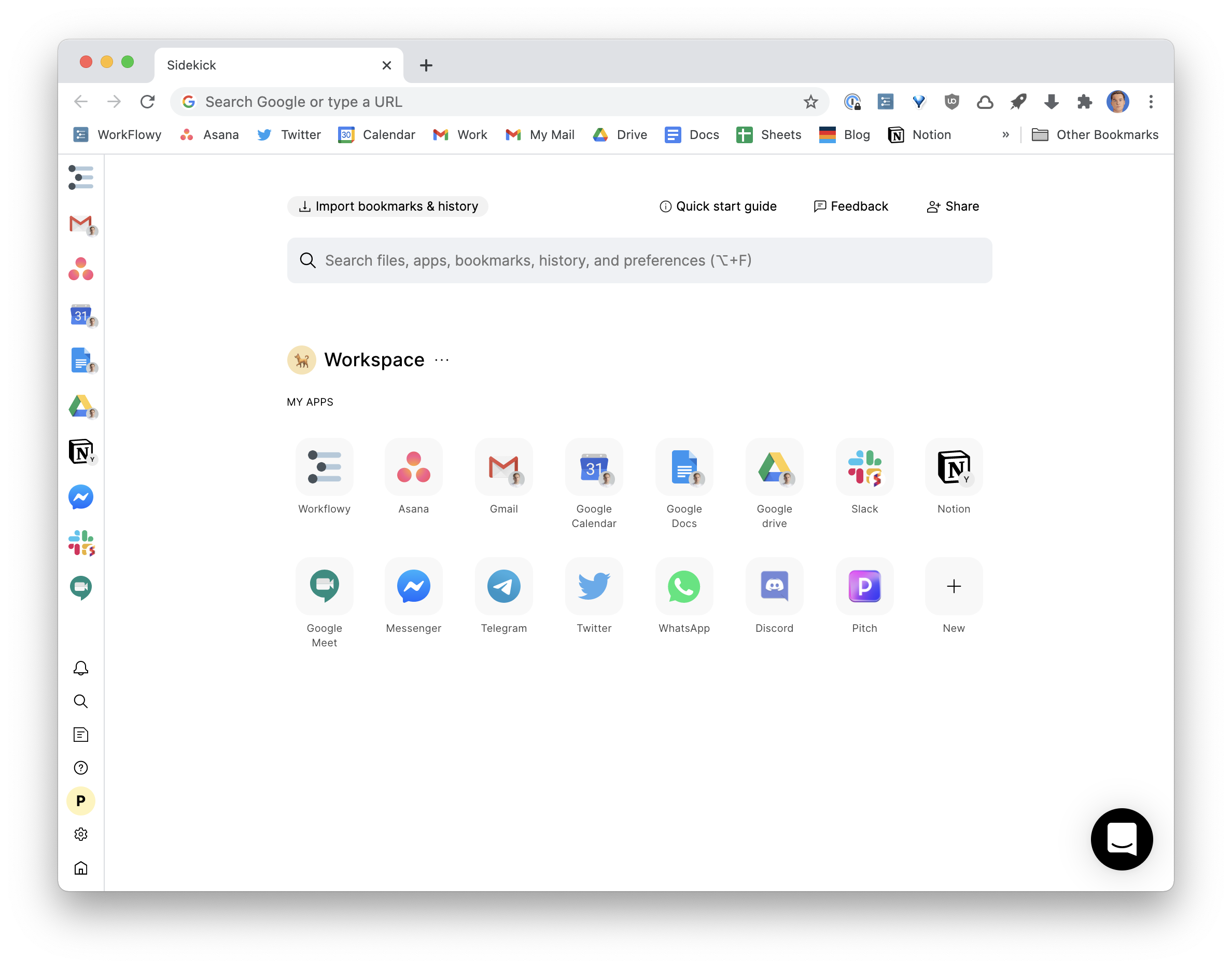

I used Arc since the beta and I loved it. Arc was the first credible and ambitious attempt to reinvent web browsing that was actually able to get some traction. Unfortunately, it didn’t get enough.

Davie Pierce covered this for the story on the original announcement of Dia:

A strange thing has happened over the last couple of years, Miller says. Arc has grown fast — users quadrupled this year alone — but it has also become clear that Arc is never going to be a truly mainstream product. It’s too complicated, too different, too hard to get into. “It’s just too much novelty and change,” Miller says, “to get to the number of people we really want to get to.” User interviews and data have convinced the company that this is a power-user tool, and always will be. On the other hand, the people who use Arc tend to love Arc. They love the sidebar, they love having spaces and profiles, they love all the customization options. Generally speaking, those users have also settled into Arc — Miller says they don’t want new features as much as they just want their browser to be faster, smoother, more secure. And fair enough! So The Browser Company faced a situation many companies encounter: they had a well-liked product that was never going to be a game-changer. Rather than try to build the next thing into the current thing, and risk both alienating the people who like it and never reaching the people who don’t, the company decided to just build something new.

Many people believe that the venture capital and the “endless сhase for growth” is the culprit here. After all, The Browser Company raised $50M at a $550M valuation in 2024. I’d say these people don’t truly understand how startups and venture capital work.

Less than 0.1% of new businesses in the US receive venture capital funding. Venture capital is intended for companies that would never be able to get a bank loan. It’s an exception, not a rule, reserved only for the riskiest bets, because 90% of startups fail within 10 years. The one and only reason some crazy people are willing to fund them is they might find the next Google or at least an Uber and earn billions. The zero-marginal-cost nature of the tech industry this makes possible: once a product works, scaling it is far easier than scaling something tied to physical infrastructure (Walmart took 63 years to reach a $700B market cap).

Most startups in any given VC portfolio fail. But you don’t know which ones will, so investors place multiple bets, evaluating what it would take for each company to become a unicorn.

Fred Wilson, General Partner at Union Square Ventures, one of the best VC firms in the game, wrote in 2016:

Our first USV fund, our 2004 vintage, has turned out to be the single best VC fund that I have ever been involved in. We made 21 investments. We made money on twelve of those investments. We lost money on nine of them. And we lost our entire investment on most of those nine failed investments. The reason that fund performed so well has pretty much nothing to do with the losses. It was all about five investments in which we made 115x, 82x, 68x, 30x, and 21x. It wasn’t like we were swinging for the fences in that fund. Every single one of those 21 investments seemed like an intelligent investment decision at the time we made it. But many of them didn’t work. We lost all or almost all of our money on over 40% of our investments in that fund.

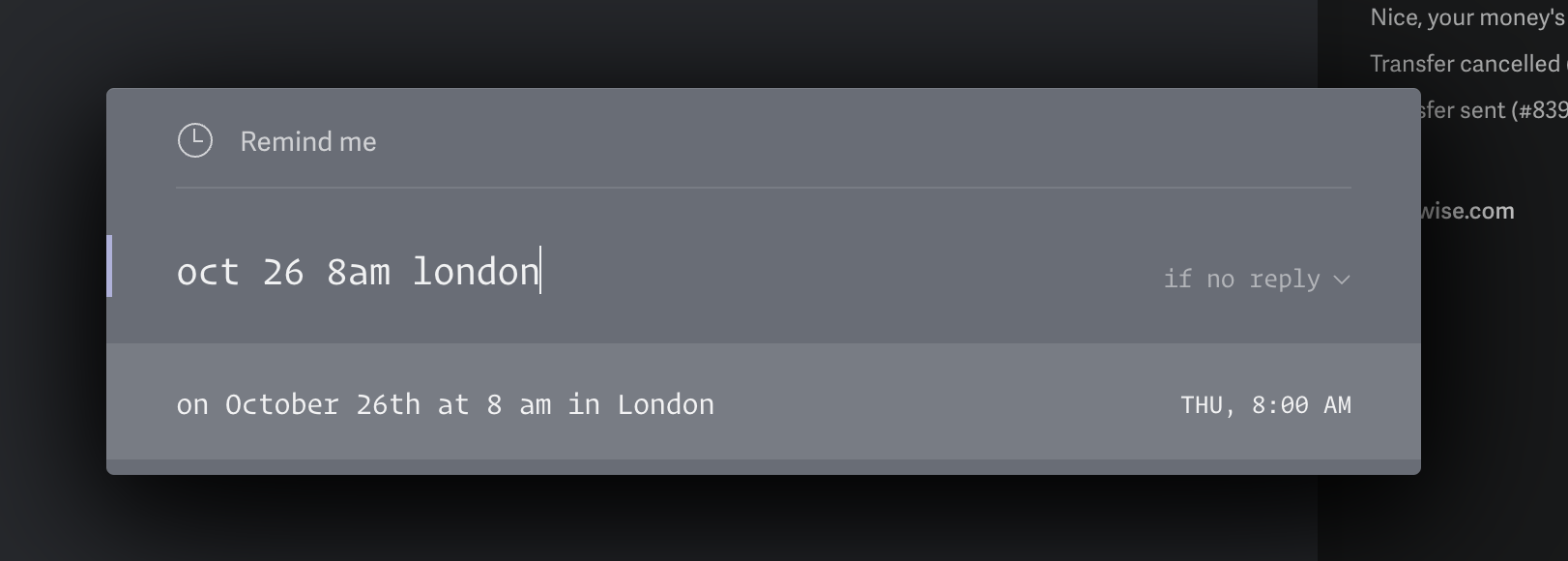

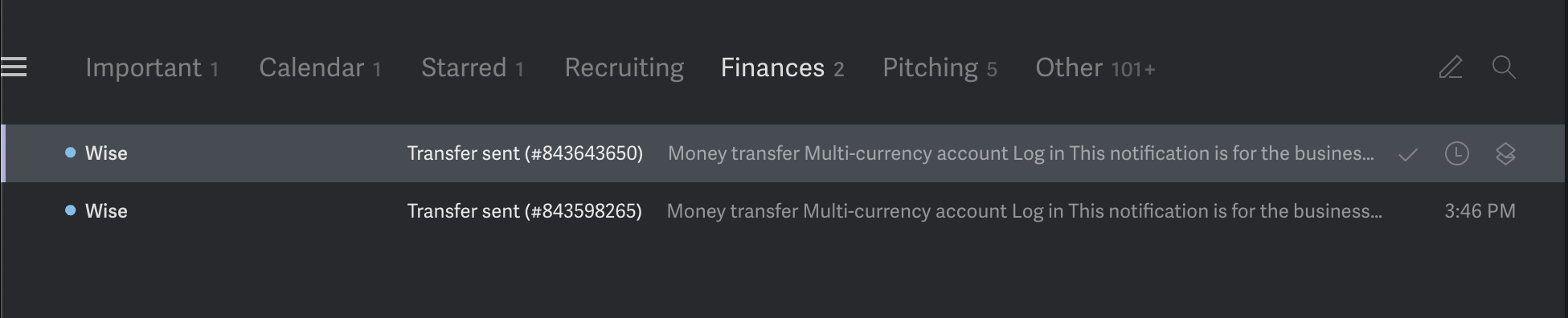

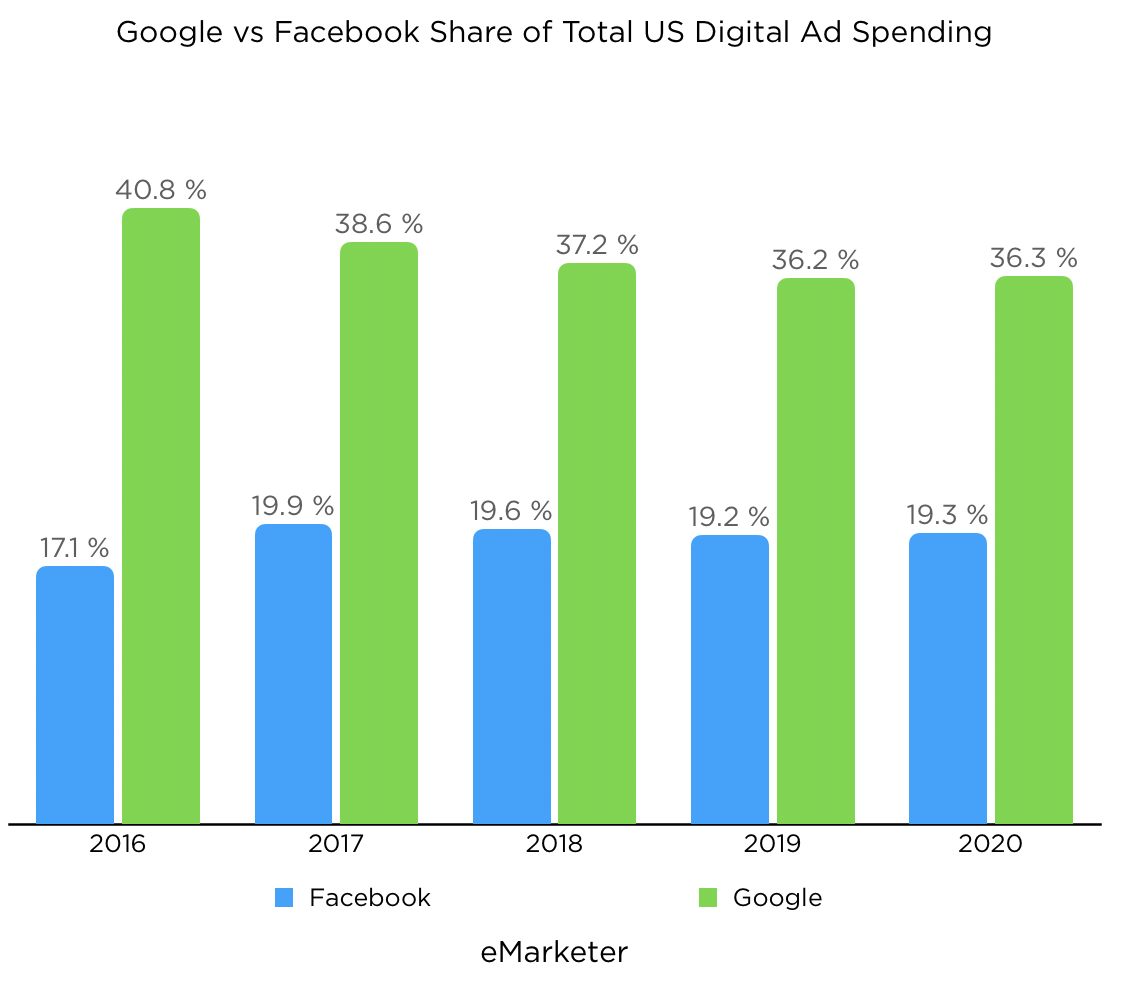

Mind me, this is the best fund of one of the best investors out there. The majority of funds don’t even beat the S&P 500. Carta published their data on the VC performance at the end of 2024:

For the 2017 vintage, for instance, median IRR fell from 16.8% as of Q4 2021 to 12.0% at the end of Q4 2024.

During that same period, the S&P grew by 2.5x—so you’d be slightly ahead if you’d gone with public markets (with full liquidity along the way).

Indeed, taking venture capital means committing to building a fast-growing product with enormous market potential. It’s not the only way to build a company, and nobody is forced to take it. In fact, anyone who’s raised funding can tell you how hard it is to convince fund managers that your startup is the next big thing.

But it might be one of the few viable paths to building a specific kind of company: one working on a truly novel product with untested technology and unclear product-market fit. One that needs to hire a full team and pay them salaries before generating revenue.

Like the Browser Company.

The same people who lament businesses for looking to grow their revenue probably care a lot about their paycheck coming on time each month. And this team has over 130 people in employment.

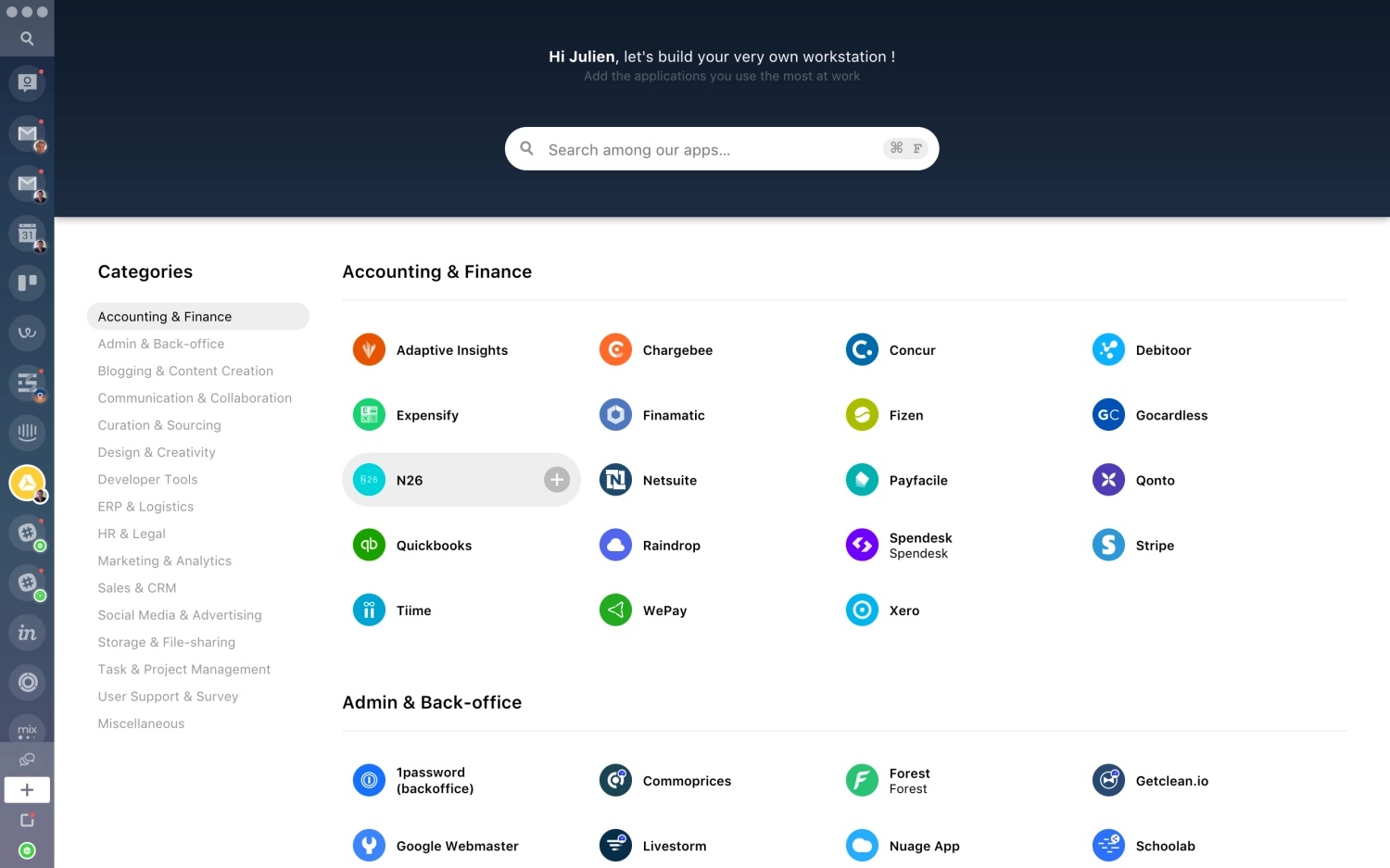

Arc was an extremely ambitious endeavour. The team went to rebuild the entire user interface from scratch, something neither Microsoft nor Brave were brave enough to do with their Chromium forks. But this unique interface built for the modern age is exactly what fueled Arc’s growth and recognition. Meanwhile, charging a subscription simply to use the product would kill it in the cradle since most of the growth was happening because of the word-of-mouth and all other browsers from big tech companies are free. Unfortunately, that also means they don’t care much about them.

The middle ground simply wasn’t possible.

***

There are many small myths around venture capital. People made wild statements based on the fact that people invest in companies, as if having Founders Fund on your company’s captable means Peter Thiel is personally making decisions for you.

Or you might point to Zed, an open-source Arc’s copycat as a counterexample to this story. Well, I’ve tried it out and I have to say that lifting 99% of Arc’s design still didn’t fix the natural roughness of consumer open source.

There are plenty of companies, even in software, that never raised venture capital, ranging from JetBrains to Basecamp, and a myriad of others you and I have never heard about. There are even unique companies that switched from a venture path to a cashflow-generating business like Buffer, who bought out their investors, and Gumroad, whose founder essentially got a gift from the investors who wrote the company off. Most successful venture-backed companies like Webflow or Figma raise funding on their own terms just to have a war chest.

Venture capital didn’t kill Arc. It gave us the chance to see what Arc could be. That’s more than most products ever get.

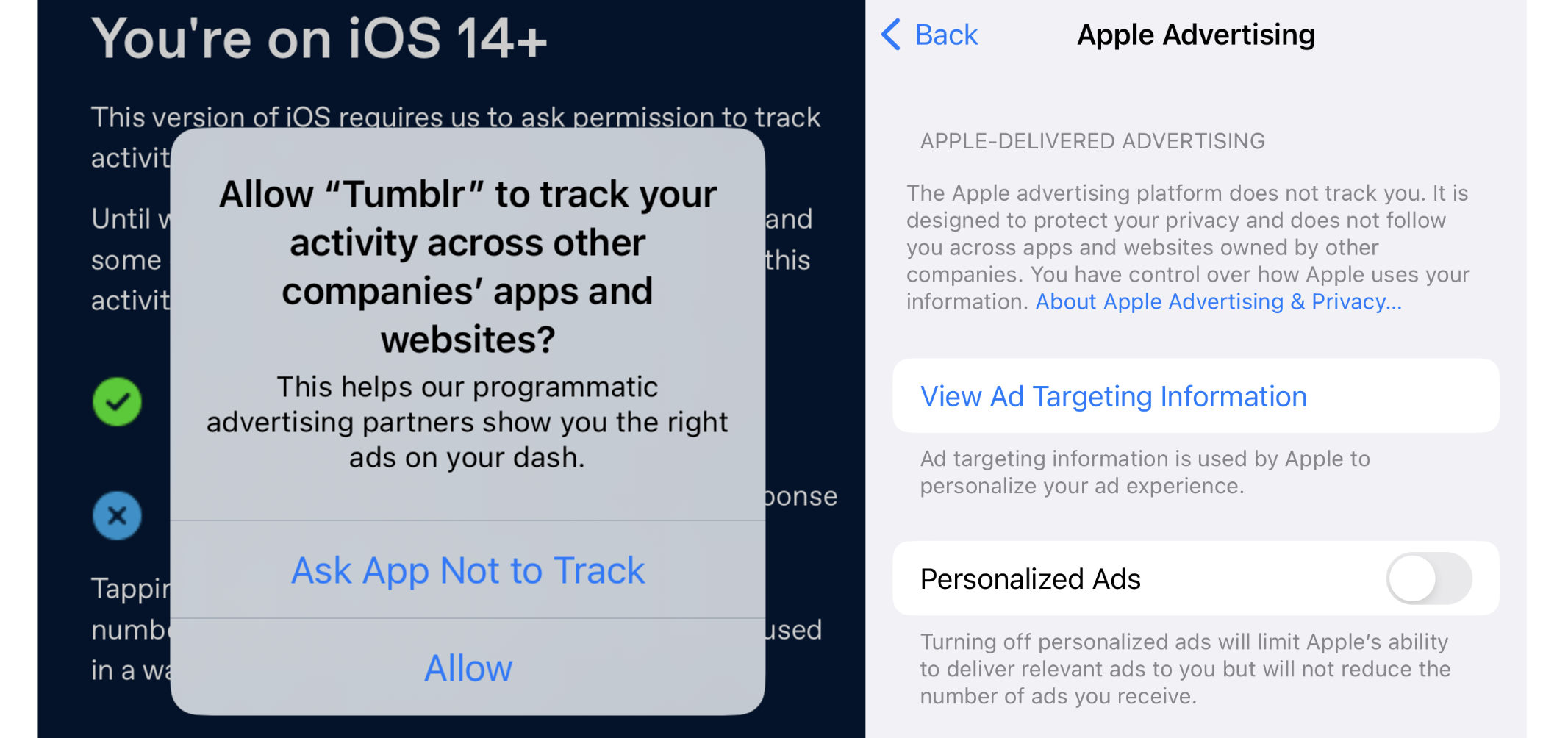

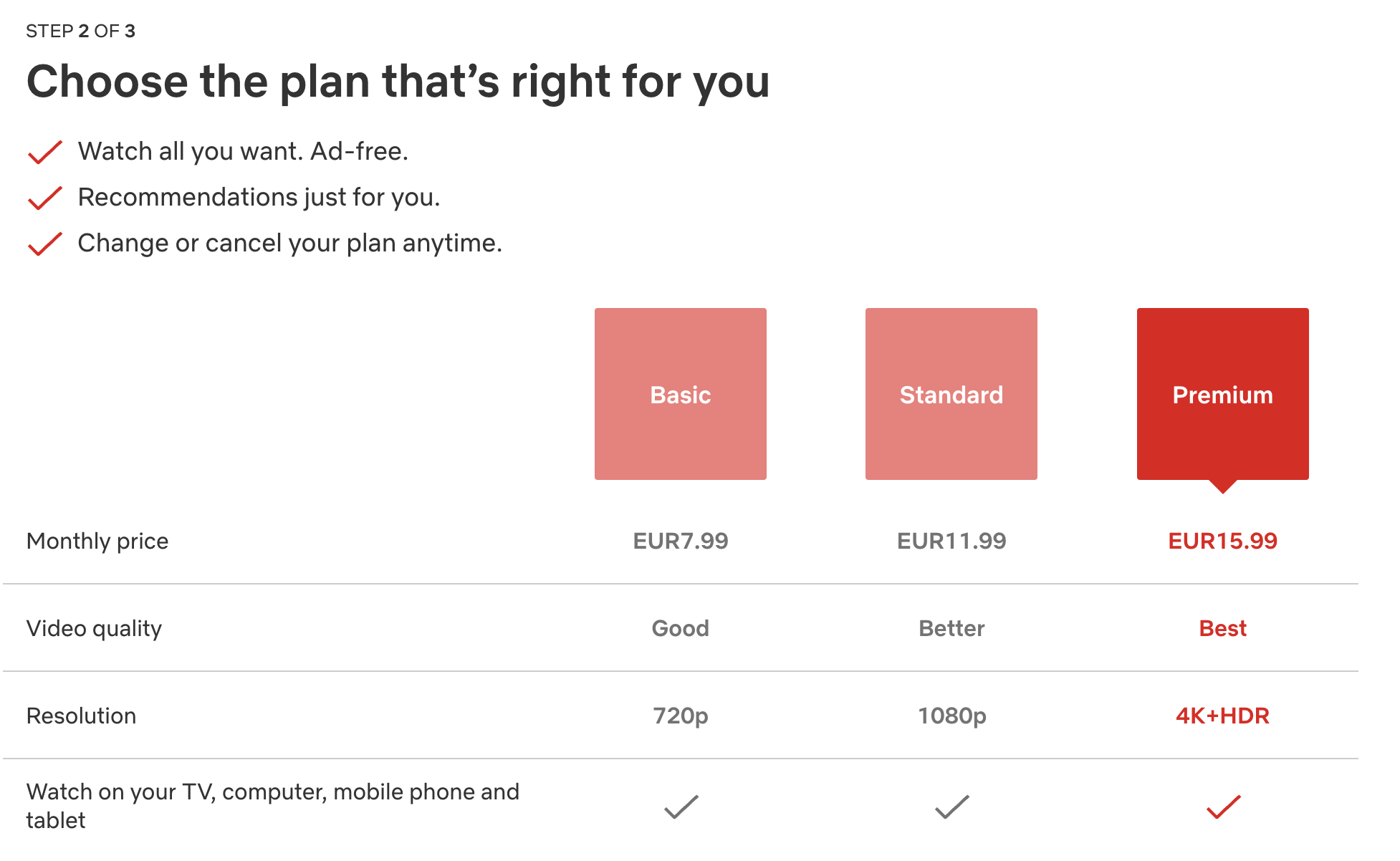

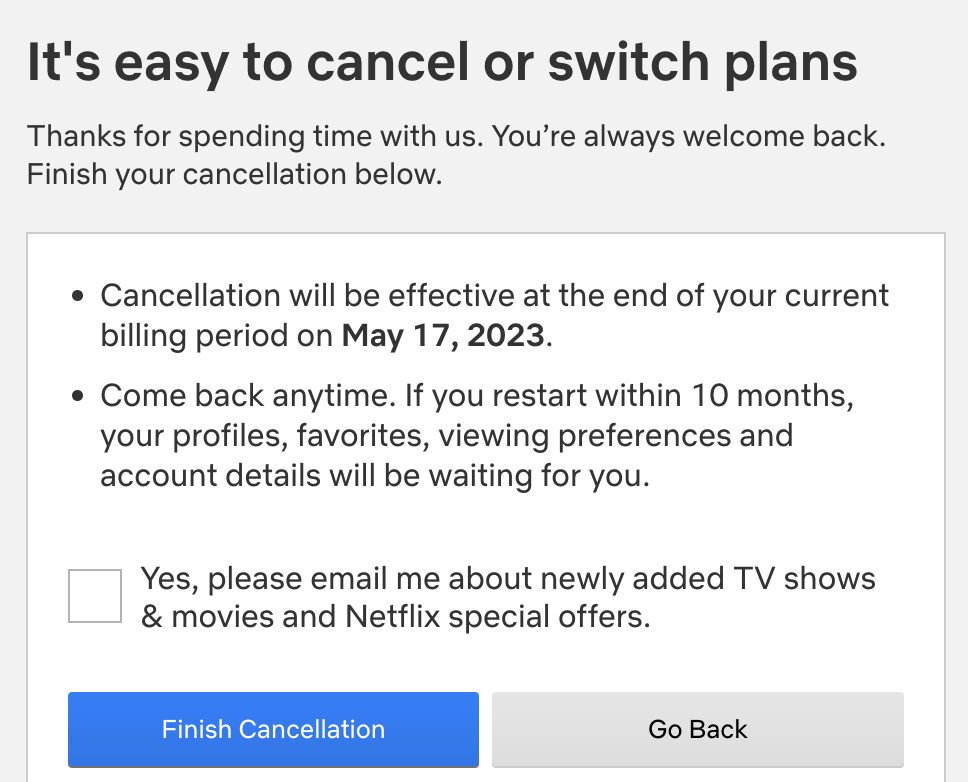

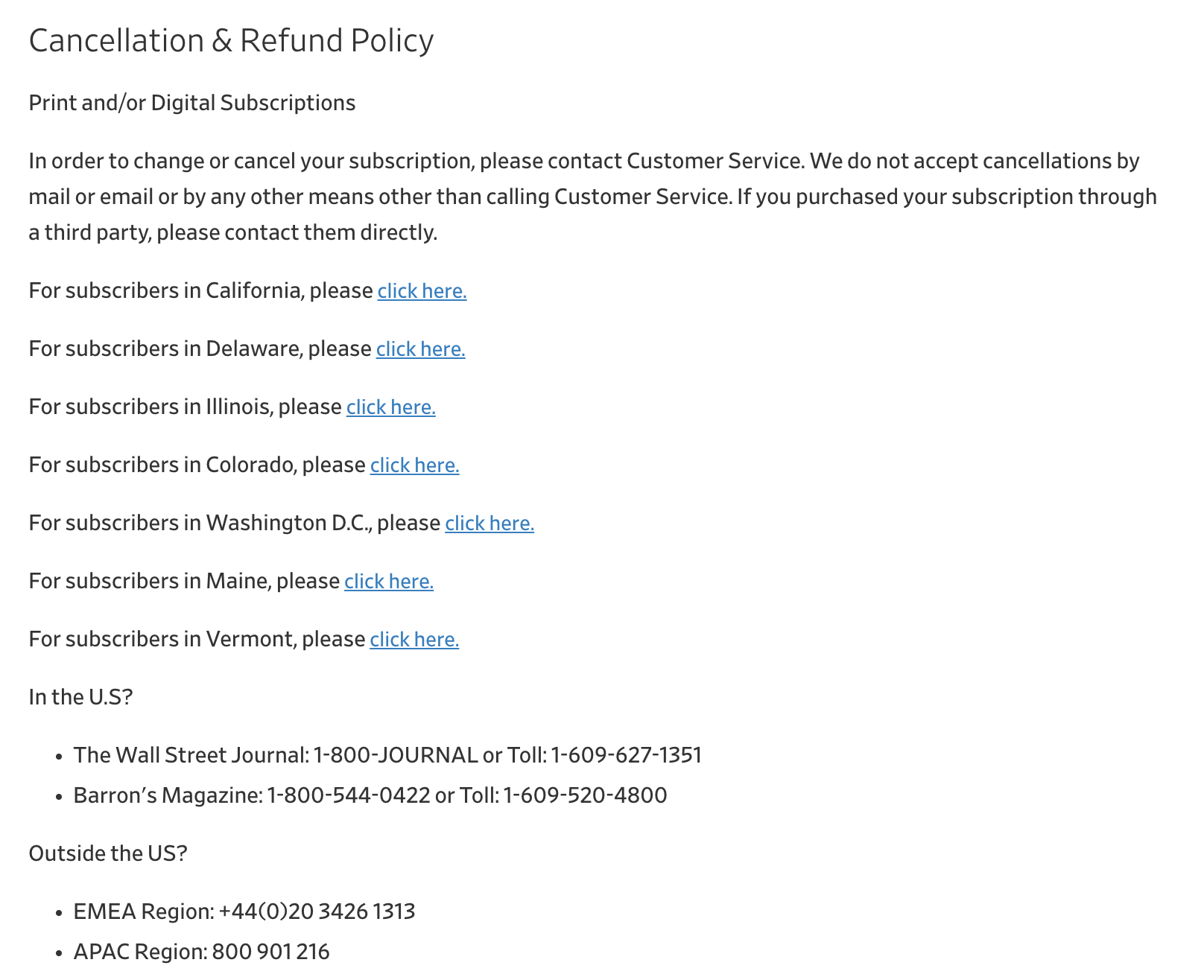

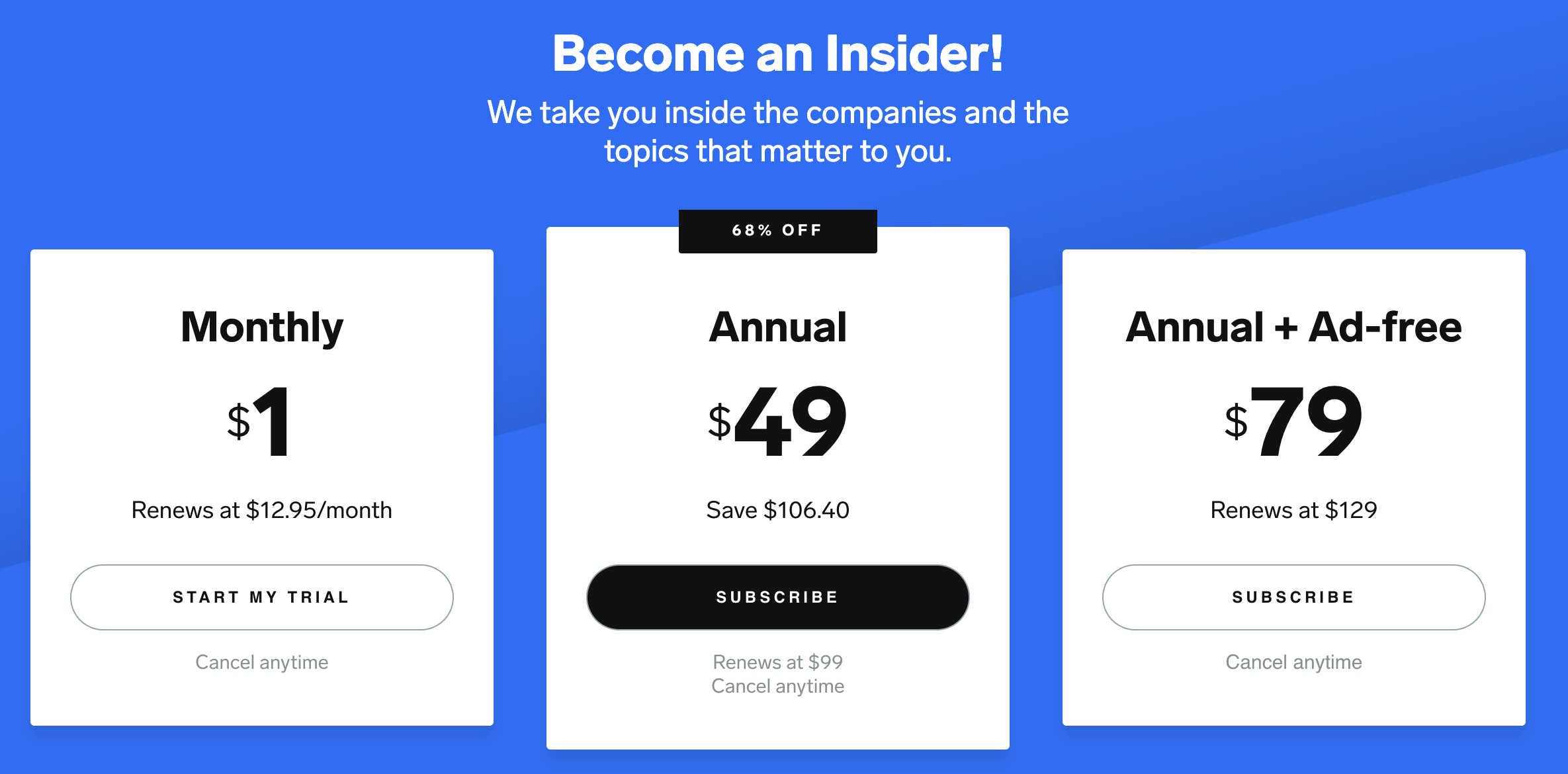

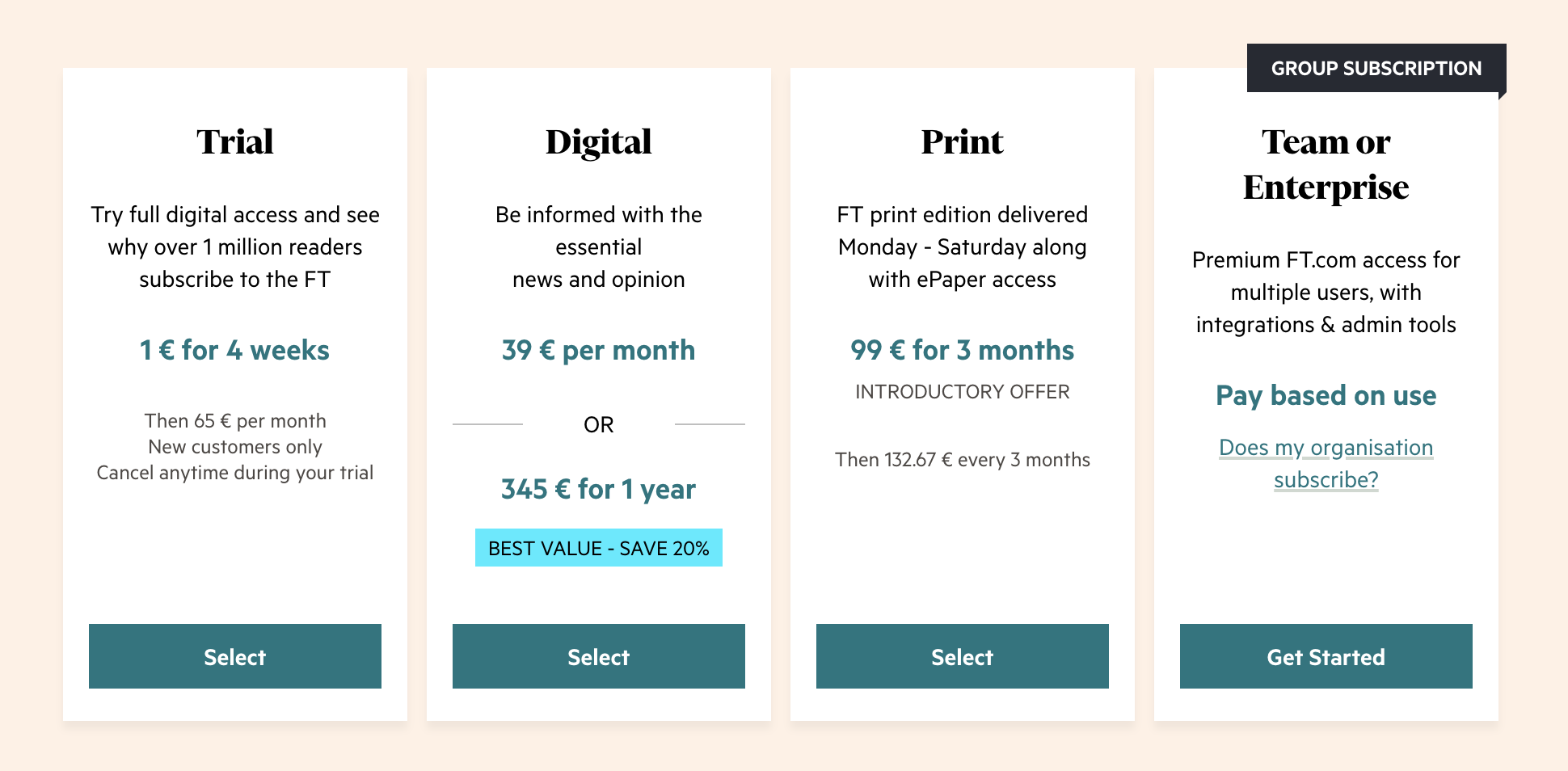

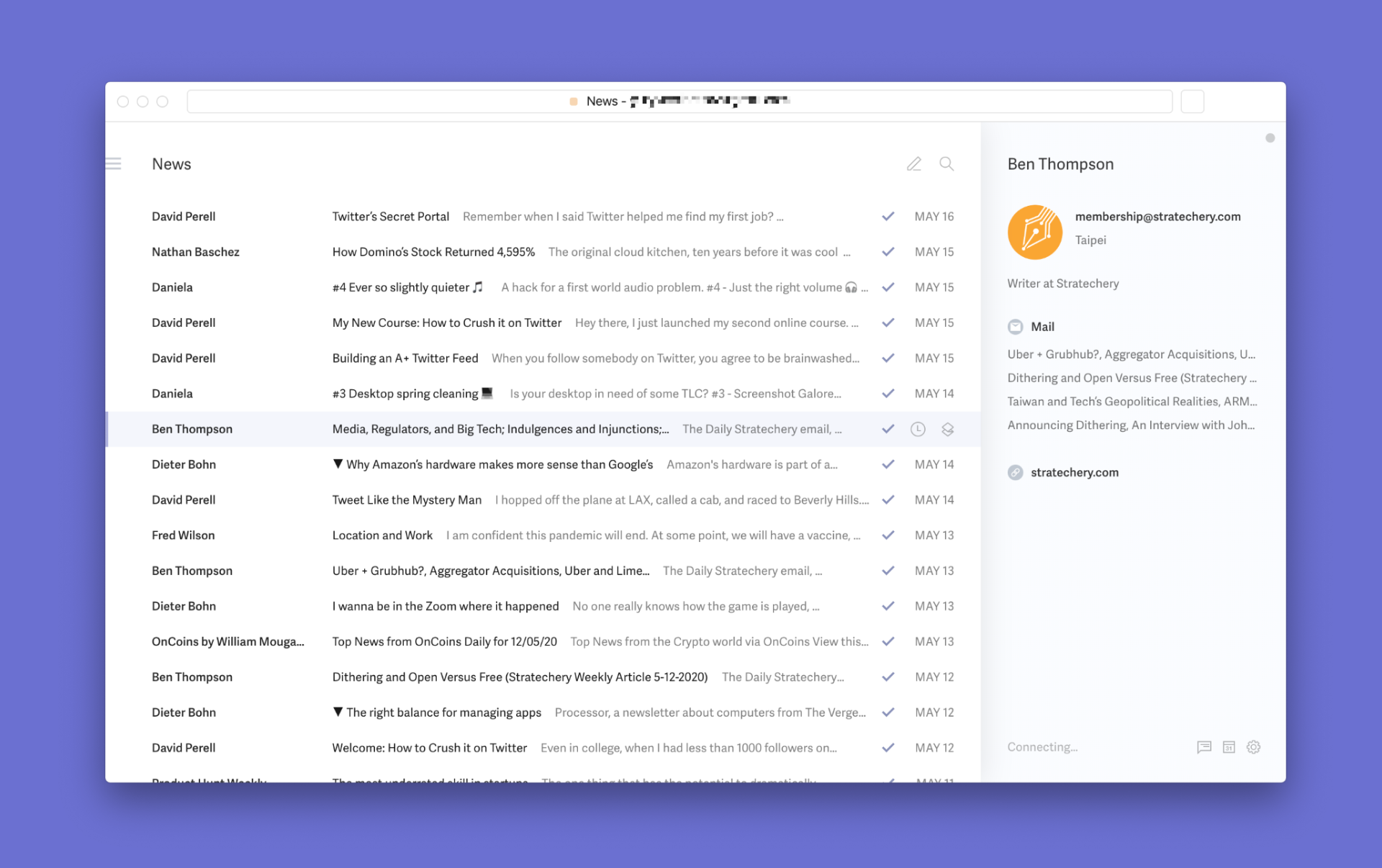

Then you have the “paywalls” themselves. Marketers at these companies try very hard to get you in and then start charging the full price afterward. The paywalls are designed to trick you.

Then you have the “paywalls” themselves. Marketers at these companies try very hard to get you in and then start charging the full price afterward. The paywalls are designed to trick you.

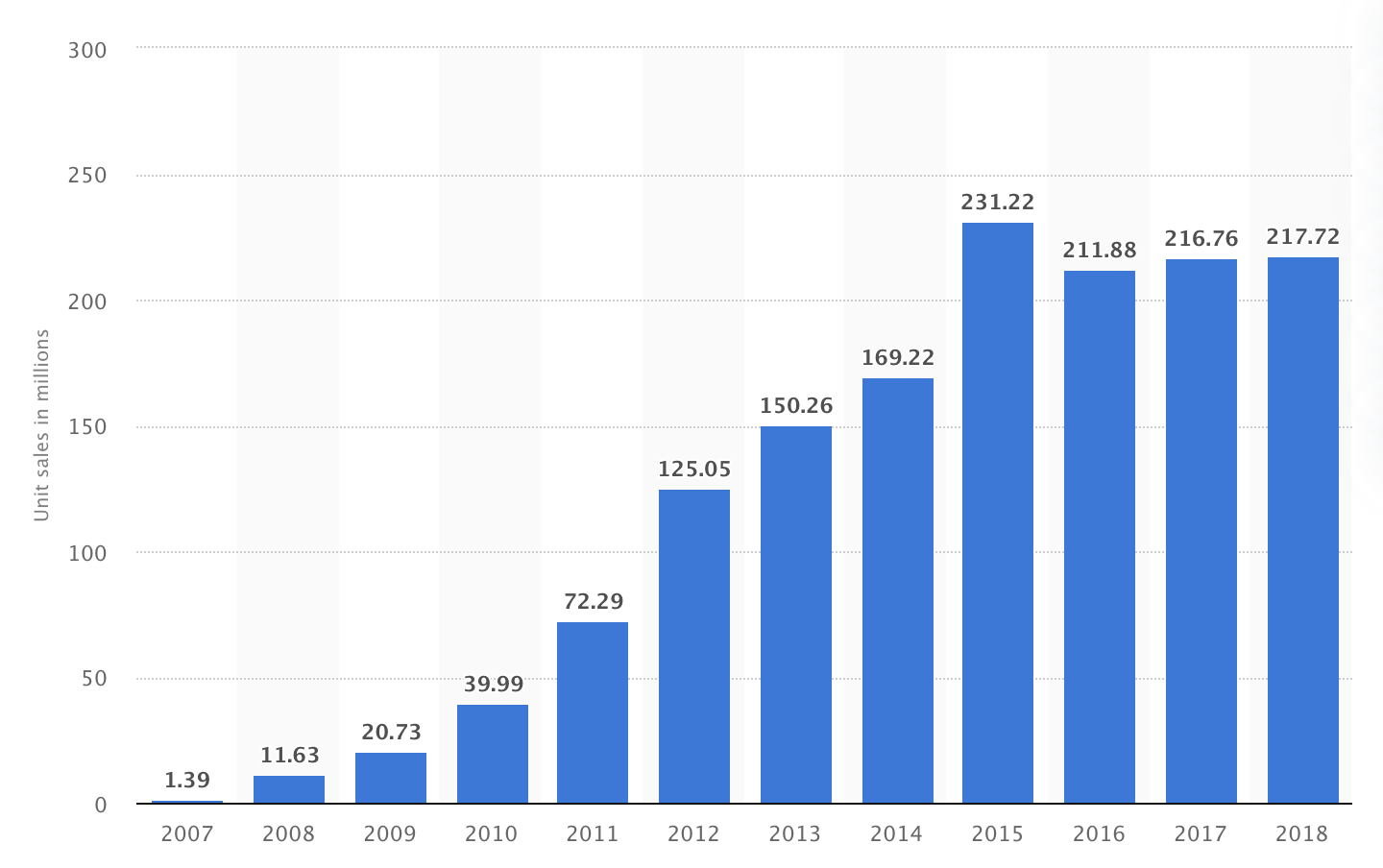

But then somethign changed. The market has become saturated. People are still buying new phones, but less often – and they already have previous iPhones (or Android phones) and had the apps they needed. One-time small purchases were no longer able to drive the revenue.

But then somethign changed. The market has become saturated. People are still buying new phones, but less often – and they already have previous iPhones (or Android phones) and had the apps they needed. One-time small purchases were no longer able to drive the revenue.